警務人員之甲基安非他命暴露與慢性疾病:烤箱淨化方法促成顯著改善

報告總結

摘要

背景:醫學文獻報告指出,反覆暴露於甲基安非他命與相關的化合物之中,將危害執法人員的健康。 雖然大多數只是短暫的影響,但有些猶他州警務人員因為勤務暴露於甲基安非他命,而產生慢性症狀,有些還導致殘疾。 這份報告是關於產生症狀的警務人員,經過烤箱淨化程序(用來減輕症狀和提升生活品質)後,所做之無對照組的回溯性病歷評估。 方法:接連參與猶他甲基安非他命警務專案的69名警務人員,在處遇計畫前後皆進行評估,處遇計畫包含循序漸進的運動、全面的營養供給,以及物理烤箱方法。 評估包含將淨化前後的研究與發展公司(Research and Development Corporation,簡寫RAND)36題健康調查短表(SF-36)評分與RAND人口常模比較、處遇前後症狀強度評分、神經毒性評分、簡易智能狀態測驗、症狀表現頻率以及處遇計畫安全性的系統評估。 結果:SF-36評估、症狀評分及神經毒性評分的統計顯示,健康狀況有顯著的改善。 淨化程序的容忍度良好,有92.8%的完成率。 結論:這項調查結果強烈意味著,參與甲基安非他命有關的執法活動而暴露於化學物質後出現的慢性症狀,可利用烤箱和營養補給來緩解。 這份報告也關係到,對於暴露於其他複雜化學物質所產生的不良反應之處理。 有鑑於此群組的臨床治療成果良好,對於烤箱處遇療程做廣泛的調查,似有其必要。

序

甲基安非他命的成癮者會出現嚴重的健康問題,但為數眾多的執法人員,因調查甲基安非他命的地下工廠,而經歷的明顯症狀,卻鮮少有人瞭解(CDC,2005年)。 雖然症狀持續時間或許短暫,但也有許多人產生持續的症狀因而尋求醫療幫助。

參與地下工廠的執法行動,相較於化學物質暴露程度較低的行動,其患病的風險被認為高出7至15倍。 根據馬歇爾的研究(2000年),自1993年以來,「調查地下毒品工廠的次數不斷增加,使得猶他州甲基安非他命工廠對上人口的比例達到全國最高。」

2007年,猶他州檢察總長調查在曼哈頓營運的烤箱淨化常規程序,此程序的對象乃2001年9月11日世界貿易中心遭受攻擊倒塌時,因參與救援與復健任務而產生慢性病的工作人員。 一名猶他州的高級警官兼專業消防隊員,因甲基安非他命工廠相關的暴露而生病,在接受這項處遇之後,健康有顯著的改善,並歸功於此。

非營利性的美國淨化基金會(ADF)建立並主持猶他甲基安非他命警務專案(UMCP),這項專案運用賀伯特淨化程序,監測猶他州警務人員的健康和生活品質,處理因職務上暴露於甲基安非他命和相關化學物質所產生的相關症狀。

研究方法:

研究組、納入條件、排除條件說明

這是針對2007年10月到2010年7月間,依序進入UMCP的前69位警務人員所做的回溯性病歷評估。 參與的警務人員是經由專案職員主動接觸、警界口耳相傳,或是由其警察局長或郡治安官轉介。

排除條件:懷孕、已知有惡性癌症、需輪椅代步、有精神病史、曾接受大量精神科治療,或曾試圖自殺,都是排除的條件。

納入條件:在猶他州進行執法工作,(2)在執法過程中有紀錄曾接觸甲基安非他命與相關化學物質,以及(3)之後產生持續性症狀或長期健康不良者,是納入的條件。 警務人員簽署處遇和成果監控(包括統計結果總體報告)知情同意書。

醫療顧問會根據參與者的綜合病史和身體檢查、心電圖、驗血結果(代謝及肝臟檢查、B型肝炎篩檢、C型肝炎篩檢、人類免疫缺乏病毒篩檢、血液常規檢查,以及甲狀腺檢查),將參與者納入研究群組。 當直接詢問時發現問題,需要進一步評估,就做進一步的檢驗,包含睪固酮的濃度等。 有衰弱症狀的警務人員可優先參加;其他諸如暴露於甲基安非他命的次數、年齡、性別或職務階級等並無特別待遇。

患者包括來自許多猶他州市郡轄區的臥底警員、毒品調查員和特種部隊(SWAT)人員、猶他州高速公路巡警(UHP)、移民和海關執法局(ICE),隸屬於美國緝毒局(DEA)的人員,以及在實驗室執行化學物質分析的人員。

介入處理措施: 標準賀伯特烤箱淨化程序。 (賀伯特,1990年)

成果評估

症狀變化和生活品質的評估,乃透過基線病史和體格檢查、追蹤訪談以及一系列處遇前後的評估來進行:

- RAND 36題健康調查短表(SF-36),評估出在處遇前,4週的健康相關生活品質。 RAND SF-36的評分機制不同於「醫療成果信託(Medical Outcomes Trust)」核准的版本,這會依日常生活能力和身體、精神狀況得出9個構面的圖表。 SF-36的評分也會將處遇前後做比較,並且與RAND美國成年人口常模做比較。

- 科學與教育促進基金會(FASE)所發展出的50題處遇前後調查,針對前4週的症狀、生病天數和睡眠模式,用以研究使用賀伯特常規程序的臨床單位。

- 根據辛格參數(Singer 2006)設計的13題處遇前後的神經毒性問卷,以0到10分的李克特式量表評定前三週的問題,包含易怒、社會退縮、動機降低、近期記憶力、注意集中力、心智遲緩/思考模糊、睡眠障礙、疲勞、頭痛的頻率和嚴重度、性功能障礙、肢體麻痺和精神敏銳度降低等等。

- 簡易智能狀態測驗。

- 每日報告表:由受過訓練的人員將每天處遇的重要徵狀/事件有條理地摘要記錄,包括任何不良效應(無論是否與處遇有關)。

為了安全性考量,程序的任何不良事件或中斷將出現在每日報告表,並由醫療顧問加以評估。

成果

處遇長度和完成率

共有66位男性和3位女性依序加入研究,平均年齡44.6歲,92.8%的完成率;其中有5位男性未完成處遇。 64位完成處遇的患者,平均處遇長度為33天。

在註冊時的評估,超過50%的警務人員出現以下症狀:疲勞:96%,失眠:91%,頭痛:90%,胃灼熱:81%,人格改變:78%,手腳麻木:77%,記憶喪失:77%,過敏史:75%,注意力不集中:75%,背痛:71%,關節疼痛:71%,出力時呼吸急促:70%,皮膚刺激:68%,焦慮/抑鬱:65%,腹脹/痛:65%,鼻竇炎/鼻塞:55%,咽喉腫痛:52%。

註冊時有異常症狀的人員比例:異常症狀包括高血脂:58%,肝功能指數升高:41%,陽性閉目難立症(閉眼時雙腳一前一後站立無法保持平衡):35%,高血壓:28%,高血糖:19%,低血液睪固酮濃度:17%,和低血甲狀腺:17%。

療程安全性

不適或其他「不良事件」(此稱呼意味著具有情緒化或類似生病的症狀)並不會對計畫執行有顯著地干擾。 例如每一位參與者皆經歷短暫的潮紅或發癢,此為菸鹼酸一般會引發的反應,但這並不影響計畫進行,也不會使參與者無法完成計畫。 如表2所示,許多參與者經歷了短暫的反應,如感覺沮喪、偶爾咳嗽、疲勞等等。 這些都是過渡性的,不需要醫療諮詢。 失眠確實會偶爾影響計畫的效果。 當前一個晚上的睡眠不足,第二天的淨化就必須縮減。 兩名警務人員痛風發作,其中一名停止了計畫。

RAND SF-36評分:

與健康相關生活品質的改變

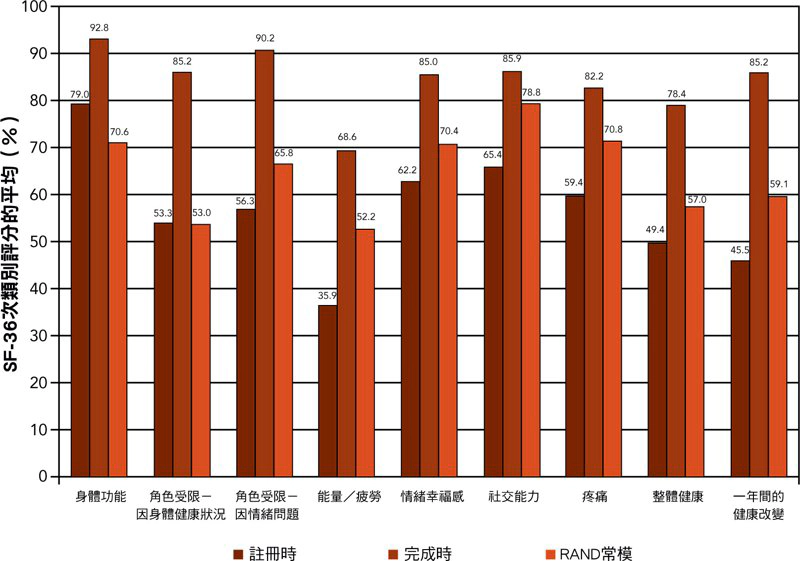

圖表2 以條狀圖顯示處遇前後SF-36評分的平均(用RAND方法計算),並且以完成常規程序的警務人員在美國人口常模的數值做對照。

警員處遇前健康相關生活品質的平均分數在所有九個次構面中明顯低於RAND人口常模,除了「角色受限-因身體健康狀況」與「角色受限-因情緒問題」以外。 在統計上,警務人員在處遇後的評分與處遇前的評分相比,有顯著的改善。 警務人員在處遇後所有次構面的評分與RAND人口常模相比,也有顯著的改善。

症狀嚴重程度與健康狀況不佳的天數

圖表3顯示處遇前後症狀嚴重程度的平均分數,與處遇前相比,處遇後分數有顯著地降低。

患者報告的平均數:

- 處遇前有9.3天身體健康狀況不佳,處遇完成時改善至1.8天;

- 處遇前有6.3天心理健康狀況不佳,處遇完成時改善至1.4天;

- 處遇前有4.3天活動因健康不佳受限,處遇完成時改善至0.2天;

- 處遇前有2.0天生病,處遇完成時改善至0.3天。

睡眠模式

參與者在處遇前平均每晚睡眠5.8小時,處遇完成時提高到7.6小時。

神經毒性的評分

此份問卷從第20位警務人員開始執行。 剔除不完整的數據,共有38組成對的處遇前後回應(84.4%回應率)。 處遇前神經毒性平均分數為65.5,而處遇後平均分數為14.6。

簡易智能狀態評估

此量表為30分制,分數低於25表示有顯著的認知功能障礙。 比較處遇前後的平均分數,並未測出改變。

問題討論

警務人員一般條件為身強體壯並且情緒穩定。 不同於適任工作的所需條件,本專案照料的警務人員,都帶有化學物質暴露而產生的慢性衰弱症狀。

在這僅僅69人的小組裡,有兩個次分組,低甲狀腺和(或)低睪固酮狀態的病患,達到驚人的17%。 甲狀腺低能症在美國的患病率約為5%。 預先存在的甲狀腺失衡可能會使警員罹患慢性疾病,但有鑑於環境化學品和低甲狀腺功能之間的因果關係,低甲狀腺狀態或許是直接導因於甲基安非他命相關的暴露。

另一不尋常的狀況,就是那些患有慢性健康不適的人,所報告的是共通的症狀。 超過75%的警務人員,回報了所有以下九種症狀:疲勞、失眠、頭痛、胃灼熱、人格改變、手腳麻木、記憶喪失、過敏症狀病史,以及注意力不集中。 這組症狀提出了一種可能性,即「共同暴露」可能引發了「共同症狀」。 此症狀模式可以幫助未來的研究者或專業處遇人員更能辨別並分類甲基安非他命相關的暴露。 暴露於甲基安非他命的警務人員在「處遇前」的SF-36分數表示比一般人有更多的疼痛、更疲勞,而且健康狀況明顯較差。

賀伯特的烤箱處遇程序是運用於此種背景之下。 如果化學物質暴露和(或)毒害造成了這些慢性症狀,那麼一項多面向的「淨化計畫」將會是合理的對應做法。

據我們所知,這是第一次以暴露於甲基安非他命的警務人員來評估烤箱式的「淨化計畫」。 絕大多數的參與者,歷經極少量的不適或不便完成這道常規程序,其症狀明顯減少,健康和生活品質有顯著的改善。 這指出這項計畫可以幫助在別處有相似暴露情形的警務人員。

| 經歷事件的人數 | 由於事件而錯過天數的人數 | 由於事件而要求醫療諮詢的人數 | 由於事件而終止程序的人數 | ||||||

| 菸鹼酸潮紅、皮膚搔癢 | 69 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 情緒化、易怒、沮喪 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 咳嗽、鼻塞、咽喉痛 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 類流感症狀、沒發燒 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 類流感症狀、輕度發燒 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 頭痛 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 失眠、清晰的夢境 | 15 | 12a | 0 | 1b | |||||

| 疲勞 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 胃痙攣、噁心、腹瀉 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 渾身痠痛 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 痛風 | 2c | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 工作或其他時間表衝突 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 3d | |||||

|

a根據程序規定,睡眠少於6.5小時的患者,第二天的處遇要縮短成10分鐘運動、4次烤箱蒸烤,每次10分鐘,蒸烤之間休息10分鐘。 b該患者在整個程序中睡眠不足,但據報有明顯的健康改善。 為了數據分析的完整性,處遇被認定為未完成。 c這兩名患者都報告,在開始常規程序之前即有痛風發作。 d兩名警務人員安排的處遇時間不足,不得不返回工作;第三名警員表明有工作相關因素,於是中止排 毒,在期間也曾錯過了6天。 |

|||||||||

參考資料:

- Alexson O, Hogstedt C (1994) The health effects of solvents. In: Zenz C, Dickerson OB, and Horvath EP (eds) Occupational Medicine. St. Louis: Mosby Press, 764–768.

- Betsinger G (2006) Coping with meth lab hazards. Occupational Health and Safety 75(11): 50, 52, 54–58.

- Burgess JL (2001) Phosphine exposure from a methamphetamine laboratory investigation. Journal of Toxicology Clinical Toxicology 39(2): 165–168.

- Burgess JL, Barnhart S, and Checkoway H (1996) Investigating clandestine drug laboratories: adverse medical effects in law enforcement personnel. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 30(4): 488–494.

- Burgess JL, Kovalchick DF, Siegel EM, Hysong TA, and McCurdy SA (2002) Medical surveillance of clandestine drug laboratory investigators. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 44(2): 184–189.

- Carpenter DO, Arcaro K, and Spink DC (2002) Understanding the human health effects of chemical mixtures. Environmental Health Perspective 110(suppl 1): 25–42.

- CDC (2000) Public health consequences among first responders to emergency events associated with illicit methamphetamine laboratories—selected states, 1996–1999. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 49(45): 1021–1024.

- CDC (2003) Recognition of illness associated with exposure to chemical agents—United States, 2003. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 52(39): 938–940.

- CDC (2005) Acute public health consequences of methamphetamine laboratories—16 states, January 2000–June 2004. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 54(14): 356–359.

- Cecchini M, LoPresti V (2007) Drug residues store in the body following cessation of use: impacts on neuroendocrine balance and behavior—use of the Hubbard sauna regimen to remove toxins and restore health. Medical Hypotheses 68(4): 868–879.

- Cecchini MA, Root DE, Rachunow JR, and Gelb PM (2006) Chemical exposures at the World Trade Center: use of the Hubbard sauna detoxification regimen to remove toxins and restore health. Townsend Letter 273: 58–65.

- Crinnion W (2007) Components of practical clinical detox programs—sauna as a therapeutic tool. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine 13(2): S154–S156.

- Dahlgren J, Cecchini M, Takhar H, and Paepke O (2007) Persistent organic pollutants in 9/11 World Trade Center rescue workers: reduction following detoxification. Chemosphere 69(8): 1320–1325.

- EHP Forum (1998) The threat of meth. Environmental Health Perspectives 106: A172–A173.

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, and McHugh PR (1975) ‘‘Mini-mental state’’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12(3): 189–198.

- Garwood ER, Bekele W, McCulloch CE, and Christine CW (2006) Amphetamine exposure is elevated in Parkinson’s disease. Neurotoxicology 27(6): 1003–1006.

- Hall HV, McPherson SB, Twemlow SW, and Yudko E (2003) Epidemiology. In: Yudko E, Hall HV, and McPherson SB (eds) Methamphetamine Use: Clinical and Forensic Aspects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 13–15.

- Hays RD, Sherbourne CD, and Mazel RM (1993) The RAND 36-Item Health Survey 1.0. Health Economics 2(3): 217–227.

- Herpin G, Gargouri I, Gauchard GC, Nisse C, and Khadhraoui M, Elleuch B, et al. (2009) Effect of chronic and subchronic organic solvents exposure on balance control of workers in plant manufacturing adhesive materials. Neurotoxicity Research 15(2): 179–186.

- Hollowell JG, Staehling NW, and Flanders WD, Hannon WH, Gunter EW, Spencer CA, et al. (2002) Serum TSH, T(4), and thyroid antibodies in the United States population (1988 to 1994): National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III). The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 87(2): 489–499.

- Hubbard LR (1990) Clear Body, Clear Mind. 2002 ed. Los Angeles: Bridge Publications.

- Kilburn KH, Warsaw RH, and Shields MG (1989) Neurobehavioral dysfunction in firemen exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs): possible improvement after detoxification. Archives of Environmental Health 44(6): 345–350.

- Leonard KL. (2008). Is patient satisfaction sensitive to changes in the quality of care? An exploitation of the Hawthorne effect. Journal of Health Economics 27(2): 444–59.

- Levisky JA, Bowerman DL, Jenkins WW, Johnson DG, and Karch SB (2001) Drugs in postmortem adipose tissues: evidence of antemortem deposition. Forensic Science International 121(3): 157–160.

- Marshall DR (2000) Report before the 106th congress: emerging drug threats and perils facing Utah’s youth. Salt Lake City, UT: Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate. http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname. 106_senate_ hearings&docid. f:73821.pdf (accessed 17 April 2011)

- Martyny JW, Arbuckle SL, McCammon CS, Esswein EJ, and Erb N (2004) Chemical exposures associated with clandestine methamphetamine laboratories. Denver, CO: National Jewish Medical and Research Center www.nationaljewish.org/pdf/chemical_ exposures.pdf. (accessed 17 April 2011).

- Martyny JW, Van Dyke MV, McCammon CS, Erb N, and Arbuckle SL (2005a) Chemical exposures associated with clandestine methamphetamine laboratories using the anhydrous ammonia method of production. Denver, CO: National Jewish Medical and Research Center. http://www.njc.org/pdf/Ammonia%20Meth.pdf. (accessed 17 April 2011).

- Martyny JW, Van Dyke M, McCammon CS, Erb N, Arbuckle SL (2005b) Chemical exposures associated with clandestine methamphetamine laboratories using the hypophosphorous and phosphorous flake method of production. National Jewish Medical Research Center http://www.njc.org/pdf/meth-hypo-cook.pdf (Accessed 9 Feb 2011).

- Miller MD, Crofton KM, Rice DC, and Zoeller RT (2009) Thyroid-disrupting chemicals: interpreting upstream biomarkers of adverse outcomes. Environmental Health Perspectives 117(7): 1033–1041.

- Rea WJ, Pan Y, Johnson AR, Ross GH, Suyama H, and Fenyves EJ (1996) Reduction of chemical sensitivity by means of heat depuration, physical therapy and nutritional supplementation. Journal of Nutritional and Environmental Medicine 6: 141–148.

- Schep LJ, Slaughter RJ, and Beasley DM (2010) The clinical toxicology of metamfetamine. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia) 48(7): 675–694.

- Schnare DW, Ben M, and Shields MG (1984) Body burden reduction of PCBs, PBBs and chlorinated pesticides in human subjects. Ambio 13: 378–380.

- Schnare DW, Denk G, Shields M, and Brunton S (1982) Evaluation of a detoxification regimen for fat stored xenobiotics. Medical Hypotheses 9(3): 265–282.

- Sharpe RM (2003) The “oestrogen hypothesis”—where do we stand now? International Journal of Andrology 26(1): 2–15.

- Singer R (2006) Neurotoxicity Guidebook. San Diego, CA: Aventine Press, 3.

- Witter RZ, Martyny JW, Mueller K, Gottschall B, and Newman LS (2007) Symptoms experienced by law enforcement personnel during methamphetamine lab investigations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 4(12): 895–902.

- Thrasher DL, Von Derau K, and Burgess J (2009) Health effects from reported exposure to methamphetamine labs: a poison center-based study. Journal of Medical Toxicology 5(4): 200–204.

- Tretjak Z, Beckmann S, Tretjak A, and Gunnerson C (1989) Report on occupational, environmental, and public health in Semic: a case study of polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) pollution. In: Post-Audits of Environmental Programs and Projects; Proceedings, Environmental Impact Analysis Research Council / ASCE. New Orleans, LA, 57–72.

- Tretjak Z, Shields M, and Beckmann SL (1990) PCB reduction and clinical improvement by detoxification: an unexploited approach? Human and Experimental Toxicology 9(4): 235–244.

- Tsyb AF, Parshkov EM, Barnes J, Yarzutkin VV, Vorontsov NV, and Dedov VI (1998) Proceedings of the 1998 International Radiological Post Emergency Response Issues Conference. Washington, DC: US EPA, 162–166, efile pages 178–182.

- Witter RZ, Martyny JW, Mueller K, Gottschall B, and Newman LS (2007) Symptoms experienced by law enforcement personnel during methamphetamine lab investigations. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene 4(12): 895–902.

- Woodruff TJ (2011) Bridging epidemiology and model organisms to increase understanding of endocrine disrupting chemicals and human health effects. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 127(1–2): 108–117.

- Wu FC, Tajar A, Beynon JM, Pye SR, Silman AJ, Finn JD, et al. (2010) Identification of late-onset hypogonadism in middle-aged and elderly men. The New England Journal of Medicine 363(2): 123–135.